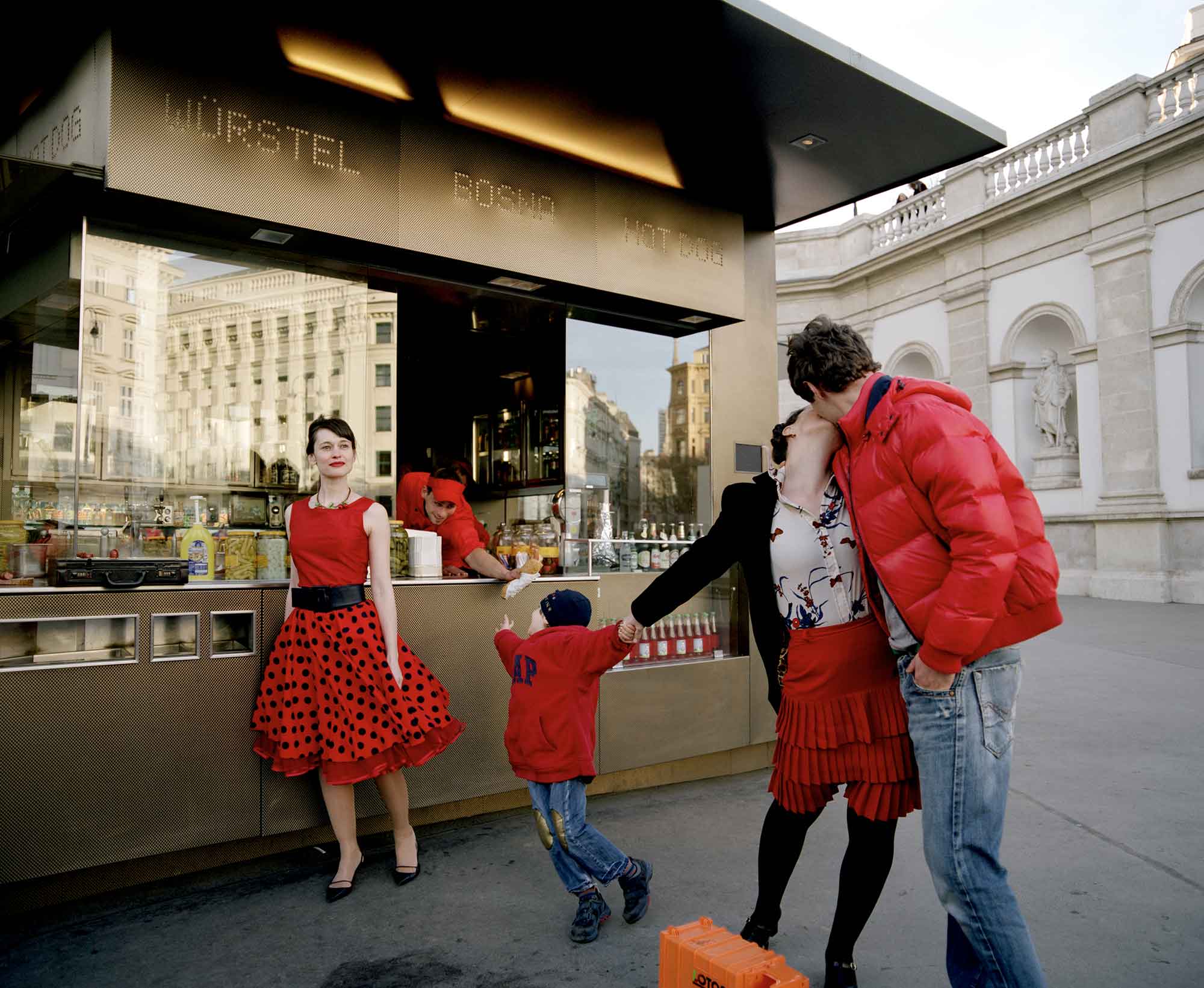

Form Follows Fiction; installation and photos: Corinne I. Rusch, 2009

/ On the state of the sausage /

The Viennese sausage stand is a brand like the coffee house or the wine tavern. But what does an original Viennese sausage stand actually look like and what should you bear in mind when designing it?

When the sausage stand in front of the Albertina was to be rebuilt, we set off with the operators on a night-time exploration tour across the city in search of role models. We traveled Ringstrasse and Gürtel, Schwedenplatz and Floridsdorfer Bahnhof for field research and drank our beer in front of cheap aluminum huts or converted steel containers, but we were fooled by the changeable character of sausage architecture, the examples did not merge into a basic type and no archetype appeared at the bottom of our sixteen-sheet. We didn’t find the traditional stand, and the myth had so far been completely without design. At least without planning design.

You have to look for the poetry around the sausage stand, it is completely covered by the many decals and advertising signs, the smell of old fat and burnt sausage doesn’t go well with it either, and sometimes the myth only shines very dimly when it is fed by stories of where Falco is said to have thrown up on Mariahilferstraße and was then ordered to clean it up by the resolute saleswoman. But the sausage stand enjoys widespread sympathy, as one speaks of a good friend who is beyond reproach. Here, the locals still have something to say: if you can order from a sausage stand without an accent and understand the cab driver’s taunts, you have arrived in the city. The cult is a relatively recent one, having entered popular culture in the 1980s, with reports in films and magazines illustrating its social elasticity and permeability, a social filling station for the urban flaneur. The sausage stand became as much a Viennese brand as the Heuriger or the coffee house.

Company gas station for the urban flaneur

Company gas station for the urban flaneur

Its development follows different paths. The smell of the markets still clings to some stalls today when they are placed in niches and pass-throughs between market stalls; at the front Naschmarkt, this can still be found at the Horvath butcher’s stall. The proximity to the butcher is obvious when the company’s own fresh sausages are cooked and sold directly. Another origin is the flying merchants and street vendors, in the outgoing In the 18th century they were called Bratelbrater in Vienna; they sold hot sausages and smoked meat from small stalls or from the windows of alleyways. Others practiced the trade with vendor’s stores and portable sausage kettles at fairs and folk festivals. In the In the 19th century, traffic junctions and busy squares were added to the rapidly growing cities, where people in a hurry ate their snacks. The water pot was heated with coal in simple handcarts; roofed and better equipped, they were gradually designed as ready-made trailers. Only in the 60s of the In the 20th century, fixed stands were permitted in Vienna. Today, Mariahilferstraße is home to the last remaining mobile stall.

Form follows function

The range is also changing. In Tante Jolesch, Torberg used to eat an apple at night at the sausage stand at Schottentor, while his quirky companion Dr. Sperber ate some Boer sausages. Until 30 years ago, the built-in sausage stove dominated the menu without restriction; the Meterburenwurst, Debreziner, Frankfurter and Waldviertler sausages floated in the water bath, invisible and hidden from hungry eyes. Then the grilled Käsekrainer began its triumphal march and today it already accounts for 70 percent of sausage consumption in inner-city locations. Form follows function: grill plates and deep fryers take up considerably more space than before and require complex exhaust systems. The stalls are transformed into small restaurants where everything can be accommodated in a very small space.

But what could a new sausage stand look like? The attempt to learn something from the existing huts, as a blameless expression of anonymous architecture, is more likely to lead to madness. In terms of design, the stands should appear open and transparent, with food and products visible and staged in display cases and windows. The stand as an object can appear symbolic, but not clumsy. The typological proximity to the beach kiosk and mobile ice cream van is greater than that to the snack restaurant. Material, lighting and lettering play a major role, allowing references and playful references to be expressed.

All this is less a question of style; intervening with planning here means above all organizing the inner life and arranging technical requirements, otherwise the prettiest outer dress will not fit well in the end because something is pushing through here and something is sticking out there. This is a fiddly job with lots of coordination and detailed drawings. At least as many companies are present at the construction meetings as for a medium-sized residential building.

It is said to have happened not so long ago at a stall at Floridsdorfer Spitz: eager tax officials observed the object in secret for a while before they then had the contents of all the dung bins spread out accurately on the ground to prove consumption within a certain period of time. You won’t find such wild tax audits today since cash registers have become widespread in stalls, partly because they are used to check employees. This is how stories can become anecdotes. One operator recounted the following episode from the 1980s, when an attack was carried out on the Hungarian bank on the corner of Krugerstraße and Kärntnerstraße and the explosion sent splinters and fragments flying in all directions, at which point the sausage seller in the adjacent sausage stand bent down to grab a mustard bucket, thus preserving his life in troubled times. The circumstances have long been forgotten, the contemporaneity has slipped into an anecdotal guise.

The appealing idea of the sausage stand as a place of communication conceals its actual function as a local supplier: this is where people in a hurry and working people eat, standing between two paths, it has to be cheap and fast, as a player in the fast food segment, a pair of frankfurters can hardly cost more than €2.90, even in good locations. Here, the family resemblance with pizza stall, kebab stand and Asian snack is particularly evident.

How do you become a sausage stand owner? Depending on the situation and size, the building authority, the market office or the municipal district office is responsible for licensing. This leaves some room for a strategic approach; one preferred way was to obtain a commercial permit for the business premises without the Department of Urban Design, MA19, having any say in the matter. As a result, many a stand was formally and legally approved without anyone feeling responsible for the overall view. For some years now, the authorities have been more attentive and new stands are hardly ever approved any more. The Chamber of Commerce currently counts 603 sausage and kebab stands in Vienna.

Instead of the plot in Döblinger Cottage, one could just as well hope for a lease agreement for a good location from the unknown hereditary uncle, near the Ring or Schwedenplatz. The operation is a catering trade without a certificate of competence, a so-called free trade. That sounds bold and proud, and in a country where so much is regulated, free trade still holds the promise of a future for newcomers and new arrivals. Quite a few operators have immigrated in this generation and mix with old Austrian sausage barns and third-generation pub operators.

Coachman’s menu and night birds

The daily chronology of a stand like the one in front of the Albertina begins at 7 a.m. when the stand is cleaned. Street sweepers and tradesmen are the first to appear, a little later the carriage drivers take their coachman’s menu, a white spritzer with a Jägermeister. The lazy morning is brought to an abrupt end at midday by tradespeople and hurried passers-by, people from the surrounding offices also lunch here standing up, and a thread of shoppers and tourists continues throughout the afternoon before some people have a small supper on their way home at the end of the office and business hours. The staff switch to a male team for the night, lively opera-goers risk the performance break for a glass of champagne outside, then the first night birds settle down, appear from somewhere, linger briefly and disappear again, cab drivers buzz around the stand at all hours of the night until the official closing time at 4am.

This chronicle is an inner-city one; at the Floridsdorfer Spitz or the Prater, other functions will come to the fore, even if the sausages are the same. As a refuge for drinkers and drifters, for example, who nobody would call strollers.

After our fruitless tour, we were perhaps left with the realization that the image of the sausage stand is a question of design and a question of narrative, form and fiction. This need not be a contradiction in terms. Both should be good. You have to be confident that new stainless steel sheets and behind unsupported glass corners will accumulate stories such as moss or verdigris. The reputation is only ever as good and lively as useful stories are in circulation, not just old anecdotes.

Sausage beat

When, on a warm Friday night last summer, two DJs were playing at the stand near Prater forecourt while an endless stream of young people rolled along in front of them between the large Prater Dome disco and the nightclub in the Fluc tub, and when, after hours of hesitantly standing around, whole clusters of these night birds finally started dancing on the asphalt forecourt until the early hours of the morning, and at some point one of the DJs reacted quickly and had the drivers of the humming MA48 dung cart brought coke and sausages so that instead of sweeping, they continued to let their yellow flashing lights sweep across the dance floor, then that was the tip of a story that somehow even pointed back to Falco on Mariahilferstraße, with less instruction and a better mood, for my taste.

Gregor Schuberth, February 2012

Published in Spectrum, Die Presse, June 29, 2012

″ Article online (Die Presse)

Anyone who can order from a sausage stand without an accent and understands the cab driver’s taunts has arrived in the city.